How data hunger and filter bubbles affect our daily lives

– about regulation & influence of filter bubbles

In 1985 my father bought his first personal computer. A black background, amber letters – it was no more than that in the beginning. He was a member of a club of techies, nowadays we would call them nerds, back then they were hobby pioneers. It wasn’t a garage in Silicon Valley, but information was exchanged nevertheless. The idea of the internet as a “shared place for everyone” was lived through and through. From my father’s lap, I witnessed the first development of the personal computer. From fascinating screensavers with trains to my own first experience with the internet, it was revolutionary.

Personalised truth

It was clear to everyone: with the arrival of the internet, the whole world would be connected. Finding information would become possible for everyone, but above all a lot easier. Everyone had access to the same information, the internet was “ours”. A democratic dream, because the available information would greatly facilitate development towards informed and empowered citizens. And it did. To a certain extent perhaps, but we can certainly state that the internet has not left our society untouched.

The contradiction, however, is that due to the same enormous amount of information, it proved to be impossible to find absolute truth. And that sometimes gets in the way of the same democratic process. The ordinary internet user lost the ability to oversee what was possible, so professional (journalistic) platforms came up to also interpret the information available on the internet. The role of journalists as gatekeepers of the internet was born. As a result, by making a selection, journalists now determined what appeared in the media, having a major influence on what we are aware of – and what not (Pariser, 2011-a).

However, trust in this profession is now declining steadily and has now reached a low point worldwide (Edelman, 2017). We prefer to look for the answer on Google or to look at the opinion of our “friends” on social media. Our search terms determine the search results, and the friends we add determine what our timeline looks like. At least, that’s what we assume.

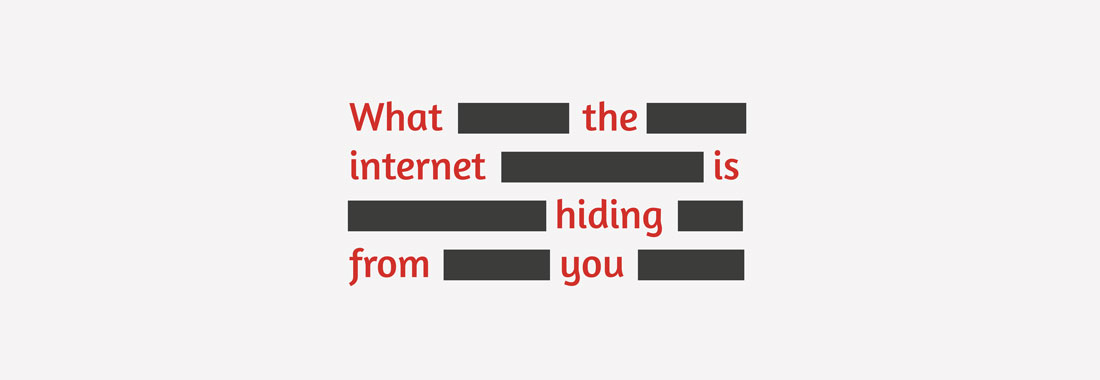

In reality, everything we see is already selected for us, based on our past behaviour. We call that “personalised”. As a result, you may get different search results, using the same keywords or some friends’ posts will appear more often than others’. Without permission, internet companies determine what is and what is not interesting to us. Even more disturbing is that you do not know what you do not see. Everything that falls outside the selection is intangible and invisible. We live in an online bubble where filters allow only like-minded people to join the conversation. The world in which we spend more and more time, the online world, is no longer about “us” – it is now about “me.” We live online in a filter bubble . [1]

Visual representation of a filter bubble.

Image: Eli Pariser’s Ted Talk.

57 “signals” and your needs for information

Your brand-new smartphone knows exactly where you are, with whom you call and how often, and what you read and listen to. Facebook knows where you click, how long you stay on a page, which friends you like best, where you go on holiday, with whom and how often. Also, the company uploads the data of all your contacts, Facebook-users or not, to its own server (Pleij, 2017). After all, you gave permission for all of this when you started using the “free” service.

The Google search engine follows every word you type, every step of the way. It uses that information to place paid ads, based on search behaviour, at the top of your results page. The other, non-paid, search results are also ranked based on the stored data. According to Eli Pariser (2011-b, p. 32), author of the book The Filter Bubble, 57 ‘signals’ are used – each of them relevant to the user’s information needs. “Signals” such as the search history or browser used, but also the physical location and time of day. And not only if the Google account is logged in: “Even if you are logged out, it will customise the results, showing you the pages it predicted you were most likely to click on” (Pariser, 2011-b, p. 34). So even if two people enter the same search term at the same place and time, the results will differ. Even the number of results differs. This creates “parallel but separate universes” (Pariser, 2011-b, p. 37).

An example from the offline world can help to explain the effect of this selection. Most parents choose themselves which school is most suitable for their children. Imagine that a family living in Amsterdam has five schools to choose from. They are free to choose, so in theory they can choose any school. If we decide that out of five schools, we won’t show three of them, they are unknown to the parents. They can still choose all schools, but they have only two left to choose from.

The freedom to make your own choices is a great asset, but external factors largely determine our choices. What can I choose from? How well informed am I? Who determines what is relevant to me? These are questions we must ask, because if a commercial company determines which schools the family from Amsterdam sees, in which order and in what way, the independence of this platform must be seriously questioned. Yet, Google determines to a large extent the environment in which we make choices, the so-called “choice environment”. Moreover, it’s telling that according to former Google CEO Eric Schmidt, the company has ambitions to provide a clear answer to just that question: “Which school should I send my child to?” [2]

Not only the Google search engine collects data. Online map service Google Maps stores where you have been, how long you have been on the road and sometimes also knows who you were visiting and for how long. For example, when using the Google address book, or if you have noted the appointment in Google Calendar. Even private emails are scanned by Google for content, to sell ads. The company has indicated that it will stop scanning personal e-mails at the end of 2017 (Greene, 2017). According to the independent tech website Tweakers, the company already stopped scanning the e-mails from companies and governments that were sent via Gmail in 2014 (Blauw, 2014).

It reminds of a quote from “The Secrets of Surveillance Capitalism,” an article by Harvard Law professor Shoshana Zuboff (2016): “Most Americans realize that there are two groups of people who are regularly monitored as they move about the country. The first group is monitored involuntarily by a court order requiring that a tracking device be attached to their ankle. The second group includes everyone else … ”

All of this data is not only used by internet companies to make money from selling it, but also to determine what users will see in the future. Third-party advertisements are offered in a personalised way, because: the more the product meets your interests, the more likely it is that you will buy it. Internet stores such as Amazon and online streaming services like Netflix invest a lot of money every year to track online behaviour. They easily earn these investments back by matching the products they offer with the interests of each individual customer. And not only internet companies understand the value of such data. The current US government can now make the application of mobile phone contacts and social media passwords mandatory for visa applications, Reuters found out (Torbati, 2017).

Roughly 2 billion of the 3.5 billion internet users are on Facebook.

Image: Niels van Velde

The youth has the future

There are almost 3.5 billion internet users worldwide (Statista, 2016). Almost 2 billion of these are Facebook users (Statista, 2017a). Facebook therefore determines for 57 percent of internet users worldwide what they see, when they see it and how they see it. Research firm Edelman concludes in the 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer that 54 percent of the Europeans surveyed would rather believe search engines than “human editors”. “In 2015, almost 40 percent of the more than nine million Dutch people on Facebook, used the social platform as a source of news,” a study into digital news consumption by Reuters revealed.

The impact is therefore considerable, especially when it comes to vulnerable groups. Newcom Research & Consultancy investigated the social media use of Dutch youth. Facebook is very popular (80 percent of 15 to 19 year-olds use Facebook). WhatsApp (Facebook Inc.) and YouTube (Google Inc.) are even more popular with 96 and 86 percent respectively (Veer, 2017). Dutch youth is therefore also influenced by the filters of internet giants such as Facebook and Google. The Netherlands Youth Institute (Nederlands Jeugdinstituut), an authority in the field of youth and upbringing issues, sees no problem, rather many opportunities in the use of media: ‘Children use online media (…) mainly to communicate with each other and share experiences, thoughts and opinions with each other. “The institute also states that these forms of interaction can take place via platforms such as Whatsapp, Facebook, Twitter and other social media.”

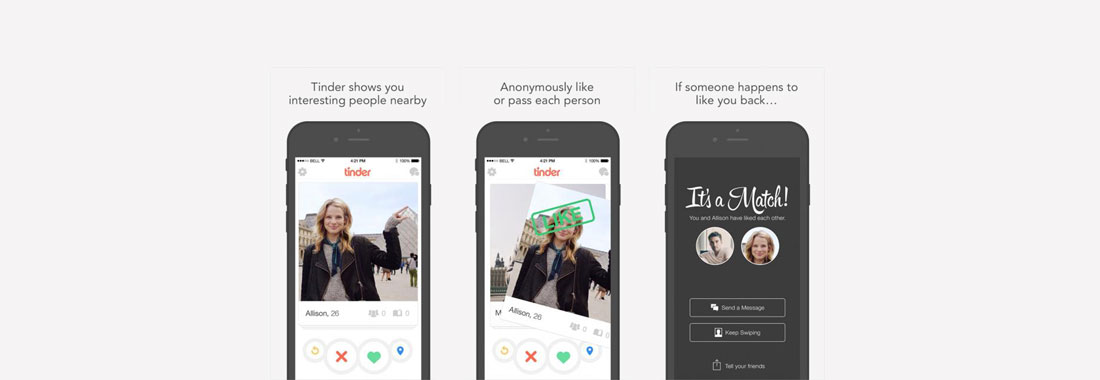

Private matters. Available for everyone

“Personal information that you don’t share with everyone.” That is how many of us would describe their sexual preferences and dating behavior. Yet we also share that en masse online. This could be seen as striking behaviour, in a society in which algorithms have enormous influence and where companies sell data by auction to the highest bidder. Where you can meet your lover not only in the bar, but also through Tinder [3] or OkCupid. [4] They also use algorithms, with impressive data sets. Tinder’s algorithm divides its users into categories, determines how “wanted” you are and uses your Facebook profile to do it. Tinder CEO Sean Rad confirmed the existence of this scoring system in a conversation with Austin Carr from the American business news site Fast Company. “It’s not just how many people swipe right on you,” he explains. “It’s very complicated. It took us two and a half months just to build the algorithm because a lot of factors go into it “(Carr, 2016). CEO Rad does not go into detail, but Carr leaves little doubt about what this “desirability score” would entail. How many of the people that you swipet to the right, do the same for you? How many do not? Do you have a high education degree, a position with prestige or are you likely to have a high salary? All information that you enter is placed on the same scale. Freely translated: how sexy is your profile? And don’t forget, every swipe is tracked, because what this simple finger movement essentially says is: “I find this person more desirable than this person,” says Tinder’s data analyst Chris Dumler (Carr, 2016). And that for just under 40 million users, spread over 196 countries – and that is for Tinder onle (Romano, 2016).

The total worldwide number of users of online dating services is difficult to estimate, but to give an impression: around 151 million (Statistica, 2017b; Statistica, 2017c) people downloaded one of the online dating apps out there (Android and iOS combined) in 2016. Badoo is the largest dating site, with 353.7 million users (Badoo, 6th of July 2017). Online dating has lost its stigma in recent years and that is reflected in the figures.

Here too, there is no proof or even the guarantee from the tech companies that they will handle the data with care, that they have no concealed motives. It would be going too far to accuse Tinder of hiding evidence, but imagine they would edit my profile based on their own beliefs or ethnicity preferences, for example? That I only got to see the singles that Tinder deliberately picked out? As far as we know this is by no means the case, but if this changes: how would we know? Tinder does not provide insight into its algorithm: “trade secret” is what they say.

Swipe to the right and find your match. Tinder knows who you like.

Image: knowyourmobile.com

Watchdog on a leash

There we again see the parallels with counterparts such as Google and Facebook. In the same way, we entrust all kinds of data, including intimate and personal data, to companies that we hardly know, whose motives are not public and that are not accountable for democratically. It is certain that algorithms largely determine what we see: “(…) which news you see, which search results you get, which sources are labeled as reliable or unbelievable and so on. In short, they largely determine what we believe, know and find, “as Rob Wijnbergen says (Wijnberg, 2016).

The controlling news media themselves, also called the watchdogs of democracy, are increasingly intertwined with social media platforms. Unintended and voluntary. Unintentionally, Google’s search results also influence the number of times an article is read. And voluntarily: even the most quality-oriented (state) media use platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn. There they share news and start a discussion with their readers or viewers. They also look at the number of views and the number of likes to judge how an article is rated. Rob Wijnberg (2016), editor-in-chief of De Correspondent, says: “Traditional news media are increasingly guided in their choices and presentation by what likes , shared or is being retweeted . At the same time, new media have emerged that are entirely based on this, ranging from mainstream (Buzzfeed, The Huffington Post) to radical (Breitbart, Infowars). In other words: Google and Facebook determine, directly and indirectly, which information is consumed in which form and to what extent. “He concludes his explanation about algorithms with the words:” Where is not true? Where is what clicks “(Wijnberg, 2016).

Based on the cover of “The Filter Bubble”

Image: Niels van Velde

Bubble criticism

An average Facebook user has access to around 1500 posts a day, but only looks at 300. That was the conclusion of Victor Luckerson (2015) in his article in Time Magazine. The platform makes a huge selection, because it certainly wants to be there that these 300 are more interesting than the rest. “Facebook says it uses thousands or factors to determine what shows up in any individual user’s feed.” (Luckerson, 2015). Other large data companies do the same. The effect of this is that we no longer see what we have to see, but only what we want to see. On Facebook we see people who look like us, to whom we have responded most often and with whom we share interests. Google “helps” us by pre-selecting information that is “relevant” to us, but does not state what it omits. Tinder promises us love at swipe distance, but hardly tells what potential matches are based on. The world around us is personalized to our own taste. What we like counts. But also: what we find is true.

That is why the criticisms listed once again:

1) Internet companies use our data for non-legitimate reasons;

2) Even if the reasons are legitimate, it is ethically questionable to use a user’s cognitive weaknesses;

3) There is a great lack of transparency where verification of algorithms is not possible.

An emotional experiment with your timeline

What Facebook thinks about ethical standards, legitimate reasons and its responsibility for the content on the News Feed, was revealed in June 2014. Researchers worked on the timeline of nearly 700,000 users to determine the extent to which emotions are “contagious” were traceable. Some of the users, without being notified, were shown a timeline full of negative status updates. Another part was full of positive messages. Not only did this research show how infectious emotion is on Facebook, but it also shows how the company lets its users run around in a treadmill like laboratory rats. Optimization of the site is the higher goal and such means are apparently allowed for this. After the fuss, I think that Facebook has mainly learned from publishing this type of research. From now on they are a little more careful with that. Whether such investigations are still taking place? Maybe right now, on your timeline. That is not difficult, with many posts people themselves indicate how they feel through “ emotion tags “. How are you feeling today?

Cognitive weaknesses of the user

An autonomous decision is, according to Karen Yeung (2016, p.7), professor at King’s College London, a decision made by a mentally competent and fully informed person. In addition, psychologists and other social scientists have repeatedly demonstrated that people who receive much different information usually do not choose rationally and wisely. They often choose the information that is simplest (Brock & Balloun, 1967) and that (re) confirm our own beliefs (Iyengar & Morin, 2006). According to research firm Edelman, it is “four times as likely” that we ignore sources of information that contradict our views or our world view (Edelman, 2017). Internet companies make use of this, perhaps unconsciously, but the impact remains large. Arguing for more initiative from the user does not seem to be a solution either: in addition to selection by algorithms, people are actively looking for information that matches their image. “People are looking for their own truth online that they would like to continue to believe in,” says a spokesperson for Hoax-Wijzer, a website that tracks the distribution of incorrect news stories (Gorris, 2016). Nevertheless, broad public information is of great importance. This is also what Marjolein Lanzing says: doctoral candidate at Eindhoven University of Technology: ‘Privacy protects freedoms that are important for a’ healthy ‘democracy, such as the development of (deviating) opinions and thoughts, various versions of the good life, experiment, creativity and unique personalities’ (Lanzing, 2016).

Acute transparency deficit

Transparency does not inspire confidence. It promotes controllability. And since reasons for trusting the privacy beliefs of internet companies are hard to find, there is a great need for them. Clear conditions with which users must agree is a first step. The problem here is that when drawing up the terms and conditions the large variety of options cannot be taken into account. This simply because some experiments arise from the availability of data. In some cases, this data causes companies to think differently about the possibilities of these datasets. Adjusting the privacy statements at that time, without asking for permission again, is a common method. The idea is that using the service is sufficient to grant companies permission to store and use the data. Offering an option to disable the effects of the change (“ opt-out “) is nothing short of rare. To do this, the user must often specify his account and its use.

A specific report for one specified adjustment could offer a solution. That this is rare is possibly explained by the fact that most hypernudges no longer work when they are conscious. Karen Yeung, the creator of the term, refers to a “Big Data” driven nudge as “ hypernudge “. This is because, according to her, this way is agile, unobtrusive and powerful, without being experienced as intrusive (Yeung, 2016, p. 6). It provides the user with a highly personalized choice environment. She also points to the great inequality between the data company on the one hand and the individual user on the other and the amount of people affected by the nudge . Facebook can exert influence on millions of users simultaneously with one (algorithmic) hypernudge (Yeung, 2016, p.7).

Data companies and their algorithms function as “ black boxes “. The code is often protected as a trade secret. The subtle way in which users are seduced is, in my opinion, one of the main reasons why citizens do not climb the proverbial barricades. If there was coercion, or rather, if coercion was experienced, internet privacy would no longer have been the exclusive domain of a selective group of critics. Organizations such as Bits of Freedom have been trying to gain a foothold in the public debate for some years, but succeed only to a limited extent because of the invisible nature of the influence exerted by such data companies.

Data hunger restricted

It’s good news from the European Parliament in April 2016: The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has been adopted. This law protects, after an implementation period of two years, from May 2018 the data privacy of all European residents. The GDPR thus replaces a law that is more than twenty years old (GDPR Portal, 2016-a).

Perhaps the most important change is that the new law applies to all personal data of Europeans, regardless of the location of the company. In other words, companies from outside the European Union must also comply with the legislation as soon as they collect or use data from Europeans.

The new legislation establishes a number of rights for ‘ data subjects ‘ (individual users): first, the right to a notification as a breach of security in all likelihood results in a risk for individual rights and user freedoms. The Netherlands already has such legislation, which is regulated by the Data Leak Reporting Act that came into force in January 2016 (AP, zd. -a). Secondly, the right to receive the collected data, free of charge and in a readable format. Third, the right to “be forgotten.” An individual hereby acquires the right to determine, in addition to viewing the data, that it must be deleted or excluded from further use. As far as I am concerned, it is an appropriate way to promote equality between digital giants such as Google and Facebook on the one hand and individual users on the other. It is also a first step to curb the abuse of power by data companies and that is desperately needed. Less than two months ago, on May 16, 2017, the Dutch privacy watchdog, the Dutch Data Protection Authority (AP) published a report on the use of personal data by Facebook. The AP concludes that Facebook uses “special data of a sensitive nature”, such as sexual orientation, religion-related search behavior and health-related search behavior, without explicit permission. (AP, 2017, p. 163) Facebook also does not adequately inform the user about “the continuous tracking of a significant percentage of their surfing behavior and app use outside the Facebook service, even if they are logged out.” (AP, 2017, p. 156) ) Restricting the amount of data collected is good news in the fight against filter bubbles. Fewer data and fewer opportunities to personalize, although that is probably only a short-term effect. In my opinion, this report and this new law are both a reason for a greater impact in the future to think differently about the influence that we want, or dare to give, data companies.

To determine to what extent this new law is capable of reducing the impact of “Big Data” on our society, I looked at the individual rights to informational privacy that apply to it. A common definition of informational privacy is that of James H. Moor: “the right to control or access to personal information” (Moor, 1989). Roughly, this definition can be divided into four elements: first, it focuses on the quest for information about someone. Secondly, it refers to personal information, whether it concerns, for example, identity, hobbies, interests or habits, or other information about the user. Thirdly, there is a certain form of control over (in this case) the data. Can the user choose which and how much information is retrieved? And last but not least: it is a right here. A right is laid down by law and must therefore be respected and protected (McFarland, etc.).

Privacy self-management

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is implicitly based on the model that Daniel J. Solove calls “privacy self-management”. (Solove, 2013) In addition, individuals are expected to make the trade-off between the costs and benefits of sharing personal data. However, there is frequent criticism of this system because it is doubtful to what extent individuals are capable of it. The following starting points are used for the argumentation of this position: 1) the rapidly changing technological landscape, 2) the fact that people generally neither read nor understand the conditions of use, 3) the inability of users to understand the impact of data sharing to estimate accurately and 4) the inability to oversee the multitude of data.

1) A landscape in which innovation is sometimes a goal rather than a means, that is how the internet could be described today. The options seem to be expanding every day, including the effects on users. Staying up-to-date and a constant guarantee of your personal privacy is an illusion, if the responsibility lies with the individual. Comparative research with each change must then show whether the user still agrees with the conditions. When the changes are made and in what form, is not known in advance. In my estimation, the GDPR does not offer a solution for this, because an active approach of the user about specific changes and impact is not explicitly required.

2) In 2008, scientists McDonald and Cranor estimated that it would take approximately 244 hours a year to read all the terms we accept (McDonald & Cranor, 2008). That is more than 30 working days per year. In other words, it is much more understandable that the majority of users press on agreement, without having read what they agree with. In addition, we can state that reading the conditions in full is strongly discouraged. This legally formulated document, often dozens of pages long, can hardly be called understandable. This endless “ terms and conditions “, full of incomprehensible and legal language, must disappear, the EU Parliament concluded. Permission to collect and use data must be clear and the withdrawal of consent must become easier. The conditions must be drawn up in concise and clear language. It is important to mention the warning that Professor of Media, Culture and Communication and Computer Science at the University of New York, Helen Nissenbaum, expressed in her essay “A Contextual Approach to Privacy Online”. In spite of the aim to prevent information overflow, simplifying communications also leads to insufficiently detailed information provision, with the result that people are insufficiently able to make informed choices (Nissenbaum, 2011, p. 59).

In addition, the question remains whether or not the conditions are readable, readable texts or not. In various studies on this subject, including the aforementioned Lorrie Cranor in which creative and practical solutions were offered, this proved to be insufficient (Yeung, 2016, p.9). More reassuring is the additional measure described in the General Data Protection Regulation under the name “Privacy by design” (GDPR Portal, 2016-a). The Dutch Data Protection Authority says the following about this: “Privacy by design means that as an organization you first pay attention to privacy-enhancing measures during the development of products and services. (…) Secondly, you take data minimization into account: you process as little personal data as possible, ie only the data that are necessary for the purpose of the processing ”(AP, etc.). Furthermore, the GDPR prescribes a restriction on access to personal data.

3) Exactly how vulnerable are you when strangers watch your data usage? That is not a simple question to answer. The majority of people are aware of, for example, the sensitivity of bank details, identity papers or sexuality-related details, but a lot of discussion is often possible outside of them.

Many individual decisions are made on the basis of unconscious, passive thoughts, rather than active, conscious deliberation. That is the conclusion of the Israeli-American psychologist Daniel Kahneman (2013) in his international bestseller Thinking, Fast and Slow. In addition, it appears that the privacy-related behavior of individuals is strongly influenced by signals from the environment (Acquisti, 2015). This includes, for example, standard settings and design choices that encourage or discourage behavior, such as font size and use of color. The behavior of others also has an influence and since discussions about privacy are rarely seen as “breaking points” when using (social) media, it can be argued that this does not encourage vigilance among users. Rather the opposite is the case. Finally, we must include the influence of addiction. Social media addictions have the same characteristics as gambling addictions, with serious doubts about the ability of the individual to make a wise decision. After all, he or she is addicted (Dow Schull, 2012). Professor Joel E. Cohen of Rockefeller University in New York City is clear about the long-term effects: “Like so many addictions, our short term cravings are likely to be detrimental to our long term well-being. By allowing ourselves to be supervised and subtly regulated (…) we may be slowly but surely eroding our capacity for authentic processes or self-creation and development ”(Cohen, 2012).

4) We use many different services. Some even use hundreds of services, each with different conditions. The General Data Protection Regulation does not limit the number of services or privacy conditions, but states (as described in point 2) that these should be more limited in scope and more legible (GDPR Portal, 2016-b). However, still making a balanced and informed decision means regularly checking the terms of use of all services that have your user data. Even if we ignore the fact that users do not always know which companies have access to their data: an impossible task.

When regulating data companies in general or data collection specifically, I think policy makers should keep one basic principle in mind. The users are not the customers. What they are? This is twofold: 1) Users, as guinea pigs or laboratory rats in the treadmill, are part of a social experiment. Or, 2) they are part of the product. The platform (for example Facebook) can be compared to a factory. The user is one of the raw materials. And the companies that buy the data and base advertisements on it, those are the customers. Finally we have the victim: our collective wallet.

Manipulating an election: how does that work?

Theoretical stories about possible influence always remain at a distance. Until I read an article by Maurits Martijn (2014), Correspondent Technology & Surveillance at De Correspondent. The article is three years old, but just as relevant today as it was then: “What do you need today to manipulate elections? A media monopoly? Battle plows? Bought employees in the polling room? The control over the Google algorithm is enough. ” Martijn points to a study by research psychologist Robert Epstein (2015, American Institute for Behavioral Research and Technology in Vista, California) on influencing elections in India. “Epstein divided his test subjects (…) into three different groups. Each test subject was instructed to google the list leaders of the three largest parties in India “(Martijn, 2014). The search results were manipulated. In one group the positive articles about a candidate were at the top, in the other two groups at the bottom. No messages were omitted, so only the ranking was different (Epstein, 2015). The results were that too. According to the research, the number of votes could be increased by 12 percent in this way. In his more recent research (August 2015), Epstein said he was “able to boost the proportion of people who favored any candidate between between 37 and 63 percent after just one search session” (Epstein, 2015).

It is striking that in May 2014 the candidate who was supported by mega-group Facebook won the elections. Earlier that year, Zuckerberg (CEO Facebook Inc.) visited Indian projects several times where Facebook provided internet access. The social media staff of President Modi told The Guardian that “Facebook was extraordinarily responsive to requests from the campaign, and recalled that Das (top lobbyist of Facebook, ed.)” Never said ‘no’ to any information the campaign wanted. ” Facebook emphasized that the company “had never provided special information or additional details to Modi’s campaign” (Bhatia, 2016). It must be emphasized that it cannot be established beyond doubt that Facebook has set up an election in its own way.

The influence of votes goes far, as such actions undermine the democratic order in foundation. Even if Facebook would follow the far-reaching suggestion of Karen Yeung (2016, p. 12), professor at King’s College London, in her privacy conditions: “The content of your newsfeeds is determined by an algorithm that has been constructed in ways intended to encourage you to favor the views of political candidates favored by Facebook ”. However, in this case, after reading the terms and conditions, users can make the assessment themselves to either cancel the account or agree. This instead of being misled by the available information and especially the lack of conflicting information. Communication technology is increasingly creating our world view, says Peter-Paul Verbeek of the University of Twente: “(…) mediating artifacts co-determine how reality can be present for and interpreted by people. Technologies help shape what counts as “real.” (Verbeek, 2006, p.9)

Although increasing transparency can be a valuable addition, I want to emphasize that this does not meet the responsibilities of platforms such as Facebook and Google. But few world citizens do not use Google and a decline in use, especially due to privacy conditions, is unlikely. The service has made itself indispensable. Partly for this reason it can be doubted whether specifying the omitted information is sufficient. Professor of Law Frank Pasquala of the University of Maryland (Baltimore, Maryland) spoke in 2016 about influencing election by search engines: .) was given authority to investigate this issue (Schultz, 2016).

Summary

In this paper I showed how data hunger and filter bubbles affect our daily lives. First, I showed that personalization of information results in personalization of truths. If a society does not have common truths, it is by definition divided to the bone. The personalized selection by data companies such as Google and Facebook thus reaches the core of democracy. The most disturbing facts regarding so-called filter bubbles is that it is not possible to see on the basis of which data choices have been made and what information has been extracted. In this way, online bubbles are created in which filters allow only like-minded people to join in the conversation, without consulting the user.

Secondly, I pointed to the way in which the data companies Google, Facebook and Tinder collect data from users, even if they are considered intimate or private by the same user. The company did not want to explain the 57 “signals” on the basis of which search results are personalized when using the Google search engine (Pariser, 2011-b, p. 32). The same applies to Facebook News Feed and the algorithm that Tinder controls, these are considered “trade secrets”. To a certain extent, the specifications of these “signals” are known for extensive analysis by authors such as Eli Pariser (“The Filter Bubble”) and Sander Pleij (Vrij Nederland). Said “signals” for the Google search engine are: the search history and which browser is used, but also the physical location and time of day (Pariser, 2011-b, p. 32). Data collection from the aforementioned groups does not limit their own domain, the information is combined. Based on these so-called user profiles, data and advertising space are sold per auction.

Thirdly, I paid attention to the unprecedented scale on which users are influenced. For this I compared the population of Facebook with the number of worldwide internet users. We can also conclude that Facebook determines for 57 percent of the internet users worldwide what they see, when they see it and how they see it, as long as they are active on that platform. In the Netherlands, 80 percent of 15 to 19 year olds use Facebook. WhatsApp (Facebook Inc.) and YouTube (Google Inc.) are even more popular with 96 and 86 percent respectively (Veer, 2017). Illustrative of the number of users of online dating services are the figures of Elyse Romanp (Romano, 2016) about Tinder (40 million users, 196 countries) and the number of downloads (Statistica, 2017b; Statistica, 2017c) of one of the online dating apps in 2016 (around 151 million, Android and iOS).

Fourthly, I concluded that criticism of filter bubbles can be combined into three main points:

1) Internet companies use our data for non-legitimate reasons

2) Even if the reasons are legitimate, it is ethically questionable to use a user’s cognitive weaknesses;

3) There is a great lack of transparency where verification of algorithms is not possible.

Fifth, I placed the new European law (from May 2018) called General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) alongside the four principles of “privacy self-management”. This model by Daniel J. Solove (2013) focuses on: 1) the rapidly changing technological landscape, 2) the fact that people generally neither read nor understand the conditions of use, 3) the inability of users to share the impact of sharing of data accurately and 4) the inability to oversee the multitude of data.

In addition, I pointed out that when regulating data companies, I think policy makers should remember that users are not customers. Here I made the comparison with a laboratory and a regular production process respectively: 1) Users are like laboratory rats in the treadmill. Or, 2) users are a part of the product. The platform can be compared to a factory.

In conclusion, this paper laid the potential role of data companies in influencing elections. Search engines such as Google and platforms such as Facebook largely determine the internet behavior of users and thus play an important role in the perception of election candidates.

Niels van Velde

July 2017

Footnotes

[1] The term was introduced by Eli Pariser in 2011 in his book ‘The Filter Bubble: What the Internet is Hiding from You’. An enlightening TedTalk about the topic can be found at https://www.ted.com/speakers/eli_pariser.

[2] “Which college should I go to?” This is a statement from former Google CEO Eric Schmidt (CEO: 2001-2011) during the “Google Press Day” of 2006. Documented by Eli Pariser in “The Filter Bubble” ( p.35)

[3] Tinder is a free online dating app, focused on ease of use. Logging in is done with a Facebook account and users swipe then, per person, to the left (“nope”) or to the right (“like”).

[4] In its own words, OkCupid is “the best international free dating site in the world”. Logging in to OkCupid is done with a Facebook account or email address. Users will see a “match” and “enemy” percentage. For example, the site shows a distinction between singles that may or may not suit the user. Premium account benefits have been paid.

Literature

Acquisti, A., Brandimarte, L., & Lowenstein, G. (2015). Privacy and Human Behavior in the Age of Information. Science, 347, 509-14.

AP (2017) Research on processing of personal data of data subjects in the Netherlands by the Facebook group. Retrieved on 29 May 2017, from https://autoriteitpersoonsgegevens.nl/sites/default/files/atoms/files/onderzoek_facebook.pdf

AP (z.d. -a) Meldplicht datalekken. Retrieved on 29 May 2017, from https://autoriteitpersoonsgegevens.nl/nl/onderwerpen/beveiliging/meldplicht-datalekken

AP (z.d. -b) Privacy by design. Retrieved on 29 May 2017, from https://autoriteitpersoonsgegevens.nl/nl/zelf-doen/privacycheck/privacy-design

Badoo. (2017). Badoo is het grootste sociale ontdekkingsnetwerk ter wereld. Retrieved on 6 July 2017, from https://team.badoo.com/

Bhatia, R, (2016). The inside story of Facebook’s biggest setback. Retrieved on 20 June 2017, fromhttps://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/may/12/facebook-free-basics-india-zuckerberg

Blauw, T. (2014). Google stopt ook met doorzoeken Gmail van bedrijven en overheden. Retrieved on 1 July 2017, from https://tweakers.net/nieuws/95720/google-stopt-ook-met-doorzoeken-gmail-van-bedrijven-en-overheden.html

Brock, T., & Balloun, J. (1967). Behavioral receptivity to dissonant information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol 6(4, Pt.1)

Carr, A. (2016). I Found Out My Secret Internal Tinder Rating And Now I Wish I Hadn’t. Retrieved on 25 May 2017, from https://www.fastcompany.com/3054871/whats-your-tinder-score-inside-the-apps-internal-ranking-system

Cohen, J. (2012). Configuring the Networked Self. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Dow Schull, N. (2012). Addiction by Design. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Edelman (2017). 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer – Global Report. Retrieved on 26 May 2017, from http://www.edelman.com/global-results/

Epstein, R. (2015). How Google Could Rig the 2016 Election. Retrieved on 20 June 2017, from http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/08/how-google-could-rig-the-2016-election-121548

GDPR Portal. (2016-a). GDPR Portal: Site Overview. Retrieved on 29 May 2017, from http://www.eugdpr.org/eugdpr.org.html

GDPR Portal. (2016-b). GDPR Key Changes. Retrieved on 29 May 2017, from http://www.eugdpr.org/the-regulation.html

Gorris, H. (2016). Het Leek Nieuws, Maar Je Gelooft Nooit Wat Er Toen Gebeurde. Retrieved on 26 June 2017, from https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2016/03/22/arme-gezinnen-lopen-kans-kinderen-kwijt-te-rakenwo-1601095-a524585

Greene, D. (2017). As G Suite gains traction in the enterprise, G Suite’s Gmail and consumer Gmail to more closely align. Retrieved on 1 July 2017, from https://www.blog.google/products/gmail/g-suite-gains-traction-in-the-enterprise-g-suites-gmail-and-consumer-gmail-to-more-closely-align/

Iyengar, S., & Morin, R (2006). Red Media, Blue Media. Retrieved on 20 June 2017, from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/05/03/AR2006050300865.html

Kahneman, D. (2013). Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrer, Strauss and Giroux.

Lanzing, M. (2016). Privacy is geen luxe, maar noodzaak. Retrieved on 28 June 2017, from http://www.volkskrant.nl/opinie/privacy-is-geen-luxe-maar-noodzaak~a4379721/

Luckerson, V. (2015). Here’s How Facebook’s News Feed Actually Works. Retrieved on 26 June 2017, from http://time.com/collection-post/3950525/facebook-news-feed-algorithm/

McFarland, M. (z.d.) What is Privacy? Retrieved on 29 May 2017, from https://www.scu.edu/ethics/focus-areas/internet-ethics/resources/what-is-privacy/

Moor, J. (1989). How to Invade and Protect Privacy with Computers. The Information Web: Ethical and Social Implications of Computer Networking, Boulder, CO: Westview Press (1989): 57-70.

Nissenbaum, H. (2011). A Contextual Approach to Privacy Online. Daedalus. 140 (4), 32-48.

Pariser, E. (2011-a). Beware online “filter bubbles”. Retrieved on 26 May 2017, from https://www.ted.com/talks/eli_pariser_beware_online_filter_bubbles

Pariser, E. (2011-b). The Filter Bubble: What the Internet is Hiding from You. London, VK: Penguin.

Pleij, S. (2017). Facebookisme: het nieuwe totalitaire bewind. Retrieved on 17 June 2017, from https://www.vn.nl/facebookisme/

Romano, E. (2016). The Evolution Of Tinder: How The Swipe Came To Reign Supreme

Tinder. Retrieved on 25 May 2017, from https://www.datingsitesreviews.com/article.php?story=the-evolution-of-tinder-how-the-swipe-came-to-reign-supreme

Schultz, D. (2016). Could Google influence the presidential election? Retrieved on 29 June 2017, from http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/10/could-google-influence-presidential-election

Solove, D. (2013). Privacy Self Management and the Consent Dilemma. Harvard Law Review 126, 1880-93.

Statista. (2016). Number of internet users worldwide from 2005 to 2016 (in millions). Retrieved on 26 June 2017, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/273018/number-of-internet-users-worldwide/

Statista. (2017a). Number of monthly active Facebook users worldwide as of 1st quarter 2017 (in millions). Retrieved on 26 June 2017, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/264810/number-of-monthly-active-facebook-users-worldwide/

Statista. (2017b). Most popular Android dating apps worldwide as of July 2016, by downloads (in millions). Retrieved on 25 May 2017, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/264810/number-of-monthly-active-facebook-users-worldwide/

Statista. (2017c). Most popular iOS dating apps worldwide as of July 2016, by downloads (in millions). Retrieved on 25 May 2017, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/607160/top-ios-dating-apps-worldwide-downloads/

Torbati, Y. (2017). Trump administration approves tougher visa vetting, including social media checks. Retrieved on 20 June 2017, from http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-immigration-visa-idUSKBN18R3F8

Veer, N. van der. (2017). Social media onderzoek 2017. Retrieved on 26 May 2017, from http://www.newcom.nl/index.php?page=socialmedia2017

Verbeek, P.-P. (2006). Materializing Morality: Design Ethics and Technological Mediation. Science Technology & Human Values, 31, 361.

Wijnberg, R. (2016). Waar is wat klikt. Retrieved on 26 June 2017, from https://decorrespondent.nl/5951/waar-is-wat-klikt/2207847791402-5166b30f

Yeung, K. (2016). ‘Hypernudge’: Big Data as a Mode of Regulation by Design. Information, Communication & Society. Volume 20, 2017 – Issue 1: The Social Power of Algorithms.

Zuboff, S. (2016). The Secrets of Surveillance Capitalism. Retrieved on 20 June 2017, from http://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/debatten/the-digital-debate/shoshana-zuboff-secrets-of-surveillance-capitalism-14103616.html